Our central student admin team emailed me earlier this week with a request: a student wants to enrol in my course, three weeks late. A third of our ten-week term has already passed, an assessment is due the very day they’d be enrolled, and the course itself is a prerequisite for their degree. Normally, late entry isn’t allowed. But as I read their email, a question echoed in my mind: What’s the kind thing to do?

It’s a deceptively simple question that many of us, especially those who advocate for kindness in academia, try to centre in our decision-making. And at first, the answer seemed obvious. Letting them in would be kind, right? It would give them a chance to complete their degree on time rather than face delays.

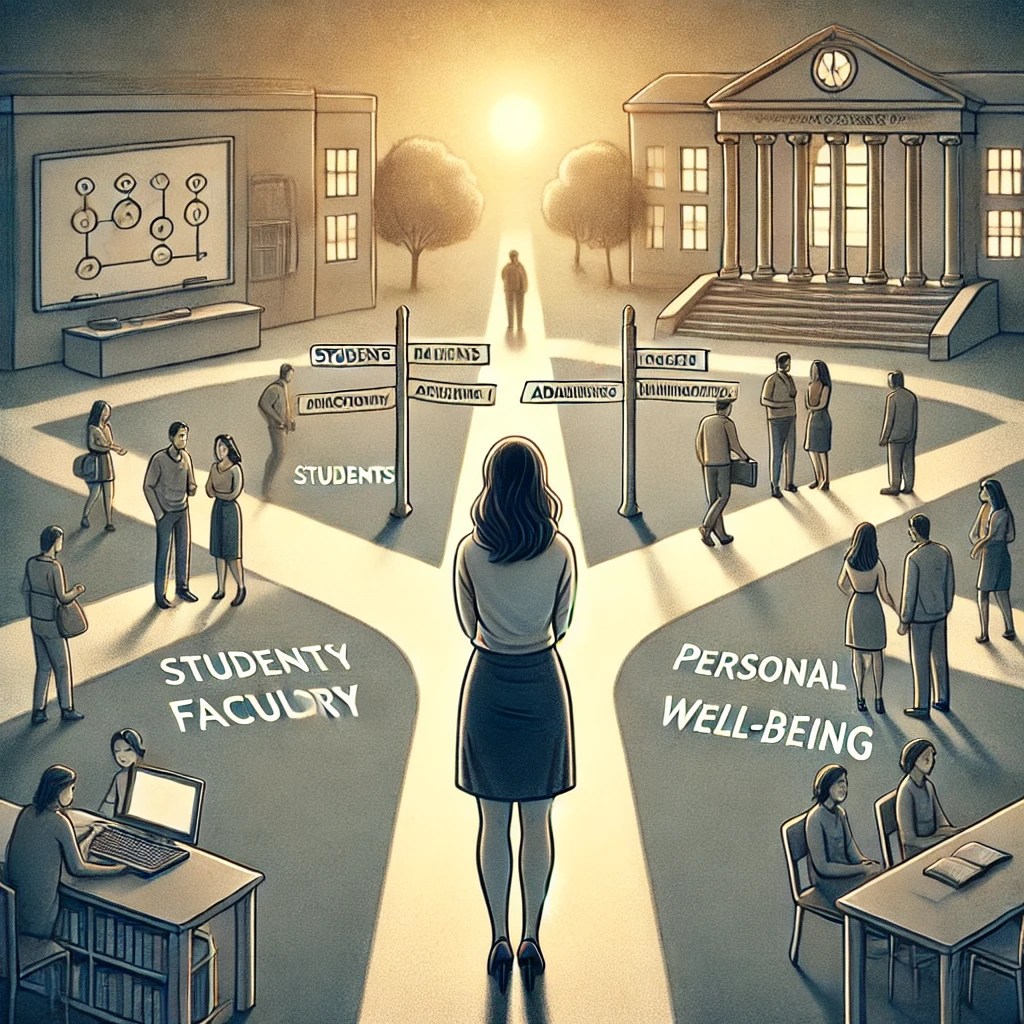

But the more I thought about it, the more complicated it became. Because kindness isn’t just about the person right in front of us. It’s multi-layered. It exists in an ecosystem. And when we only consider kindness at an individual level, we risk being unkind elsewhere.

Kindness for whom?

If I admit this student, what does that mean for the others?

- What about the 800 students already in the course, who have attended lectures, engaged in discussions, and met deadlines? Is it fair to them to allow a latecomer to bypass the same expectations?

- What about my tutors, who will have to integrate a new student, catch them up, and mark their work separately? In a large-scale course, even one exception creates an administrative ripple.

- And what about me? As much as I want to support students, I also have to acknowledge that my time and energy are finite. Is it kind to myself to add another layer of complexity to an already enormous course?

It turns out What’s the kind thing to do? isn’t a simple question. It’s a balancing act. A negotiation. A messy, imperfect attempt to hold space for multiple competing needs.

The challenge of kindness in higher education

This dilemma speaks to a broader challenge in embedding kindness into academic decision-making. It’s not just about being kind, it’s about being equitably kind. It’s about recognising that different stakeholders (students, tutors, faculty, administrators) experience policies and decisions differently.

So how do we navigate this? What’s the formula for knowing when kindness should be extended to an individual versus upheld for the collective? And when does kindness to one person inadvertently become unkindness to others?

I don’t have the answer. But I do know this: kindness in academia cannot be a single act. It has to be a way of thinking that accounts for the broader system we operate in. And maybe the challenge isn’t in finding the right decision but in being willing to sit with the complexity, knowing that true kindness isn’t always easy, but it is always worth considering.

Leave a comment